My

thanks to Prof. Jun Nogami of the University of Toronto Dept. of

Materials Science and Engineering , adviser to its HPV team and head

timer at the Battle Mountain event for allowing me to use photos and

some information for this report from his blog, “Biking in a Big

City.” To see his extensive reporting on and photos of the event,

go to https://jnyyz.wordpress.com.

There’s

also a report there by Evan Bennewies, who was the back half of the

University of Toronto’s Titan, which set a tandem record.

By

Mike Eliasohn

The

20th annual World Human Powered Speed Challenge outside of Battle

Mountain, Nev., held Sept. 8-14, drew a record number of entrants,

with 17 vehicles, and 29 riders, compared to 13 vehicles and 20

riders last year.

Among

them were Mike Mowett of Detroit, who shared (not at the same time)

his Velox X-S streamliner with Ishtey Amminger of Memphis, Tenn., who

has competed at the Michigan HPV Rally every year since 2015.

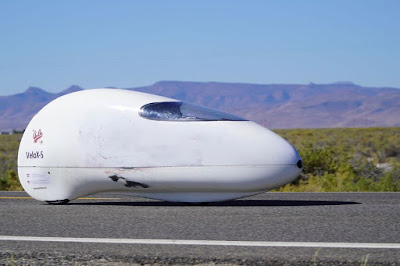

Ishtey Amminger in the Velox X-S gets closer to the junior record on this 63.7 mph run.

Mike

bought the streamliner, constructed by Hans van Vugt of the Netherlands, in

January 2018 from Garrie Hill of Granville, Ohio. Since then came

many changes, improvements and modifications, which continued at the

event. Peter Amminger (Ishtey's father) and Mike worked on average

about six hours a day on the Velox – in between and after the two

sessions of races in the morning and evening. Mike said the

amount of work, little sleep, and the long 2,000 mile drive to get to

Battle Mountain in two days really sapped his energy from racing

during the week.

The

Velox X-S team consisted of, from left, brothers Willam and Ishtey

Amminger, their father, Peter Amminger, and Mike Mowett.

Competitors

have a 5-mile run-up on State Road 305 before entering the 200-meter

timing zone. The elevation is 4,619 feet, so the resulting thin air

reduces air resistance.

Mike’s

goal, after competing at Battle Mountain three previous times, was to

finally go 60 mph. He made four runs, finally hitting 60.53 mph on

Saturday morning and earning a 60 mph hat.

Ishtey’s

goal was to exceed the junior men’s (age 15-17) record of 65.93

mph/106.10kph, set by Florian Kowalik of Deerfield, Ill. (a past

Michigan HPV Rally competitor) at Battle Mountain in 2016, riding the

same Velox X-S (then owned by Garrie).

Ishtey

made 11 runs during the week and exceeded Florian’s record on

Friday evening at 66.67 mph and Saturday evening at 66.6 mph. but

both were classified as wind "non-legal', so were not official.

(Under International HPV Association rules, to be legal, the wind

cannot exceed 6 kph/[1.67] meters per second in any direction.) And

he’s 17, his last year of eligibility for the junior record.

Mike

Mowett made one run without the top half of the fairing, which gives

an idea of the interior layout. He and Ishtey are both about 5’10”,

so both could ride the Velox X-S without seat or crank adjustments.

Incidentally,

the fastest the Velox X-S has gone is 70.27 mph, piloted by Ellen van

Vugt (Hans’ wife) at Battle Mountain in 2012.

That

leads to the question, if the X-S “peaked” in 2012, why did Mike

and Peter have to do so much work to prepare the bike for Battle

Mountain this year. Here’s Mike’s much abbreviated (and edited)

answer: When Ellen rode the Velox X-S, it

was set up very well by Hans. Then it was stripped apart and sold to

Garrie in 2013, with just basically then body, no wheels, no

drivetrain and no seat.

Garrie

requested it that way from Hans, so he could just get it cheap, and

Garrie had this plan to change the bike from a rear-wheel-drive to

front-wheel-drive with twisting chain.

Mike Mowett is inside, pedaling furiously, during this qualifying run.

Mike Mowett is inside, pedaling furiously, during this qualifying run.

Garrie

did start making parts for the Velo X-S, but he got behind

in his plans and Florian really wanted to ride it for the junior

record. In 2016, as it was Florian’s last year as a Junior.

Garrie

started putting the X-S back together as it was originally

designed. Garrie had to cut and narrow the front and rear wheel.

Unbeknownst to him, both of these wheels had major issues not

discovered until this year by Pete, Hans and I. Hans pounded the heck

out of Garrie’s wheel to shift it about 5 mm sideways to take care

of the high speed shake we were having.

Garrie

built a seat which put pur heads too high, wedged against the top to

the point of being unsafe to ride. After I talked with Garrie he

quickly sent me another seat with a more lower and laidback design

that solved this.

Fran

Kowalik (Florian’s father) and others at Battle Mountain made a

huge effort in a very short time to get something together for

Florian to make those runs and set the record in 2016. It was all

cobbled together and only like four gears worked, when nine gears

should have worked.

All

that got torn out and I started over in July and had something

working after trying six different derailleurs, then grinding a

derailleur, the body and the derailleur mount to finally get one

derailleur to shift across 10 of 11 gears. At Battle Mountain we had

to manually put the chain on the 11th gear (the lowest and easiest

gear) before we started. This worked.

Beyond

that, Pete and I, along with Hans, added a front wheel shroud that

Hans originally designed, and his lower rolling resistance tires. BUT

the biggest thing the bike still lacked was a set of $500 each super

low rolling resistance Michelin radial tires that Ellen probably

used to go 70 mph back in 2012.

There was one other competitor from Michigan, Andrew Sourk of Detroit in his homebuilt Triage three-wheeler (above).

There was one other competitor from Michigan, Andrew Sourk of Detroit in his homebuilt Triage three-wheeler (above).

After

first competing with his machine in 2016 and completing only one run

at 18.6 mph, Andrew made many improvements, his goal this year being

to make it to the end of the course. He succeeded in one of three

runs, reaching a speed of 28.72 mph.

On

the following run, his wheels developed an oscillation, which caused

him to crash in the speed trap. He finished the run by

carrying his vehicle across the finish line. Jun Nogami reported Andrew "knows now that his trike has a tendency to shake itself to pieces around 30 mph," so hopefully he will keep working to improve it.

Andrew Sourk (left) of Detroit, with his father, who helped him during the Speed Challenge, at the awards banquet.

Andrew Sourk (left) of Detroit, with his father, who helped him during the Speed Challenge, at the awards banquet.

During

the week, three riders exceeded the women’s record of 75.69 mph,

set by Barbara Buatois of France in 2010. Coming out on top, on

Friday evening, was Ilona Peltier at 78.61 mph in Altair 6 from the

Annecy University Institute of Technology in Annecy, France.

Mike

Mowett, wearing his 60 mph hat and the 2019 World Human

Powered Speed Challenge T-shirt (artwork by C. Michael Lewis).

Here’s

some of Mike’s comments after he got home to Detroit, emailed to

Mike Eliasohn:

Basically

after the 2,000 mile drive for me and 1,800 miles for The Ammingers,

Pete (Ishtey’s dad) and I spent the next six days and nights

working on the Velo X-S. All told I think our days ran from about

6:30 a.m. wakeup to get out to the course until up to about 2:30 a.m.

the next day, still working on the bike.

From

the time we arrived, the Velo X-S got new tires (donated to us by

Hans van Vugt), a front wheel alignment, also by Hans as he knows the

bike so well, having built it. This he did with a hammer and

screwdriver.

Side

note: it took me four hours and having to cut off a tire to change it

because our high performance tires were not compatible with the rear

wheel rim. We added a speedometer, GPS, video camera, walkie talkie

radio with headphones and push-to- talk button.

We

added front wheel enclosure for improved aerodynamics, along with

taping wheel openings closed with a flexible skirt made of neoprene.

We visited the local NAPA, CarQuest and hardware store for fasteners,

Bondo, paint, tape etc.

A

big problem we had to overcome during the week was having our toes

and heels hitting within the fairing. Pete brilliantly moved our

cleats around well outside the normal for a cycling shoe by drilling

new holes in the bottom of the shoes, Then finally we had to cut off

the toes on my shoes.

Later

in the week, on Friday, we upgraded the gearing, making it about 20

percent higher for more speed and that helped Ishtey and I go our

fastest speeds.

Examples

of the behind the scenes helpfulness and borrowing of parts: . Hans

set this “deal” up. I got tires from Hans and he got one of the

special $500 Michelin tires from the Italians and Ellen went her

fastest ever 72 mph and was very very pleased. The team of the second

fastest woman, from Italy, borrowed a 12 tooth gear cog off my cross

bike to allow her to go that fast.

Ishtey Amminger during the awards banquet. He's 17, so we will assume what's in the bottle is non-alcoholic.

And

here’s Peter Amminger’s report:

With

Battle Mountain 2019, I think frustrating is the best summary

I can offer.. Given the immense effort and sacrifice expended toward

reaching a goal, and then not quite delivering, can be nothing, but

frustration.

Even

though Ishtey on numerous occasions reach above records speeds, and

raced in every a.m. and p.m. session throughout the week, the goal

was just not to be had; whether because of divine intervention or

merely bad luck.

It

is especially irksome that on at least two of his fastest runs he had

by the end of the week, there was “legal” wind for the racers

running in front and behind Ishtey .....what else can I say?

I

guess I shouldn't be so hard on our efforts; it is rather remarkable

that given the multiple modifications and untested state of the bike

by Waterford 2019 (Aug. 10-11) and upon reaching Battle Mountain, and

the real lack of seat time anyone had in the bike by the start, we

had a over 95 percent launch success rate; no race “scratches,”

no crashes; had 100 percent successful runs at each and every a.m.

and p.m. racing session during the entire week; and finally that

routinely we saw speeds up to 96 percent of what this bike ever

achieved in its prime.

In

fact during one of Ishtey's runs, the session was so windy that the

officials initially wanted to, but could only technically recommend

it be cancelled. A few brave ones, including Ishtey went on to race;

here the little junior achieved by far the fastest run at 58 mph in

that pm race session, over some of the adult heavy hitters also

competing. Ishtey was literally being blown from one side of the road

way to the other while going down the track; it was terrifying for me

to watch from the following chase vehicle!

If

nothing else, the racer, the team exhibited an extraordinary degree

of determination, but alas the record was just not to be had: only

the bitter fruit of frustration....

Just

to clarify, by the time you include the short drive to and from

getting Ishtey's brother Will back to school, our travels this year

exceeded 2,000 miles each way to Battle Mountain.

This was by far the best year with respect to the drive, as Ishtey and Will together did at least half the driving combined, while I peacefully slept and rested, exhausted from my expenditure of energy during the week. We got home by 6 a.m. Monday morning, just in time for Ishtey to make his first class of the week.

Our friends at the University of Toronto weren't at this year's Michigan HPV Rally (after nine straight years) because they were busy creating the Titan tandem. They arrived at Battle Mountain on the Wednesday prior to the start of the World Human Powered Speed Challenge with a lot of work to do yet, didn't get it running on its wheels until Saturday and made their first complete run on the course on Wednesday. But their efforts succeeded. On Friday evening, they set then tandem men's record at 74.73 mph, breaking the old mark set in 2012 of 73.08 mph. Calvin Moes (fourth from left) was the pilot; the stoker (facing backward) was Evan Bennewies (fifth from left). At left is faculty team adviser Jun Nogami. (Thank you Jun for use of the photos and information from your blog.)

All the speeds recorded during the week and other information can be seen at www.ihpva.org, then at the upper right, click on "WHPSC."

The 2020 World Human Powered Speed Challenge will be Sept. 13-19 at Battle Mountain.

This was by far the best year with respect to the drive, as Ishtey and Will together did at least half the driving combined, while I peacefully slept and rested, exhausted from my expenditure of energy during the week. We got home by 6 a.m. Monday morning, just in time for Ishtey to make his first class of the week.

Our friends at the University of Toronto weren't at this year's Michigan HPV Rally (after nine straight years) because they were busy creating the Titan tandem. They arrived at Battle Mountain on the Wednesday prior to the start of the World Human Powered Speed Challenge with a lot of work to do yet, didn't get it running on its wheels until Saturday and made their first complete run on the course on Wednesday. But their efforts succeeded. On Friday evening, they set then tandem men's record at 74.73 mph, breaking the old mark set in 2012 of 73.08 mph. Calvin Moes (fourth from left) was the pilot; the stoker (facing backward) was Evan Bennewies (fifth from left). At left is faculty team adviser Jun Nogami. (Thank you Jun for use of the photos and information from your blog.)

All the speeds recorded during the week and other information can be seen at www.ihpva.org, then at the upper right, click on "WHPSC."

The 2020 World Human Powered Speed Challenge will be Sept. 13-19 at Battle Mountain.